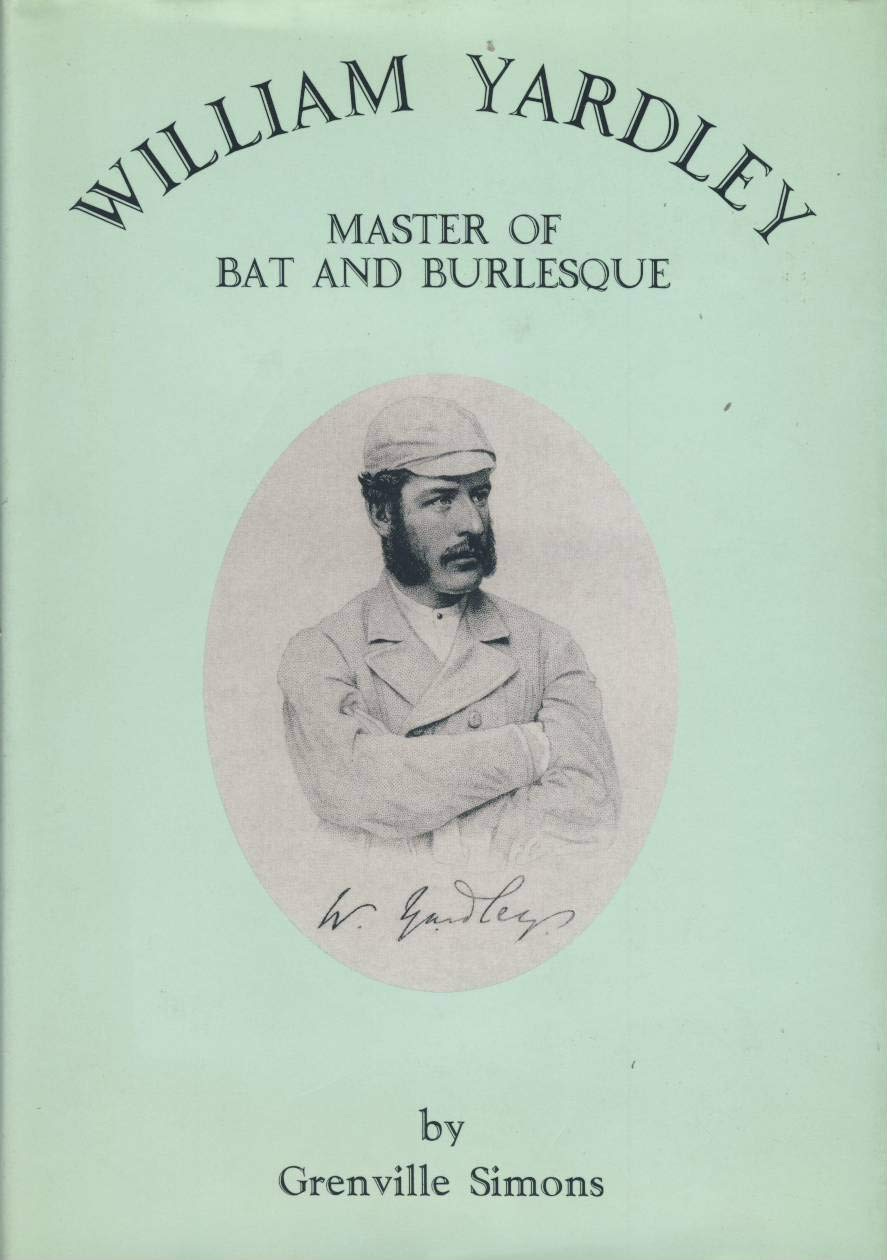

Each week we spotlight a fascinating title from the vast collection catalogued in the Cricket Bibliography project, drawing on insightful (but not necessarily positive!) reviews from the archives of our journal. Today we bring you Robert Brooke on Grenville Simons’s William Yardley: Master of Bat and Burlesque, published by Wisteria in 1997.

It is perhaps rather sad that William Yardley is a name long forgotten in cricket circles; indeed, an acquaintance whose cricket knowledge is by no means negligible once confused him with Norman Yardley, the England captain.

In fact, William Yardley, born into wealth and position in India, was one of the finest young batsmen of his or any other period. As a boy in Malabar Hill, Bombay, Yardley received his first cricket coaching from one George Place, who “encouraged” his talented charge to switch from left-handedness to right. The wonder is that William’s cricket was not destroyed then and there; it speaks volumes about his strength of character and natural game-playing ability that he became as good a right-handed batsman as he might have been had he remained left-handed. Sadly, the crude and cruel discouragement of left-handedness persists to this day—at least in England. One has even heard attempts at justification!

Yardley went on to Rugby School, where he came under the tutelage of “Ducky” Diver, a fine player and coach, but also likely an influence in other fields. Diver, like his cricketing nephew Teddy of Warwickshire, enjoyed showing off an excellent singing voice, and he may well have awakened the performing instincts in Yardley. At Rugby, Yardley took an active role in all sports, both playing and organizing. His Rugby School career is described in detail and at some length, but the inclusion—on pages 19 and 20—of a passage from Tom Brown’s Schooldays is baffling to this reviewer. The snippet grows more absurd with time, typical cant from the sort of people who urged a No. 11 fighting to win a match to “play up, play up, and play the game.” The same ludicrous advice was offered to a regiment fighting for its very survival with “The Gatling jammed and the Colonel dead,” according to Henry Newbolt.

Yardley continued his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was fortunate to have E. W. Blore—a well-known classicist and a cricket “Blue”—as his tutor. His time at Cambridge was largely triumphant; after a quiet start in 1869, he became the scorer of the first University match century in 1870 and, two years later, achieved the second. He also played well enough for the Gentlemen to suggest a marvellous career—some even thought he might challenge W. G. Grace. But it was not to be. Upon leaving Cambridge, he played occasionally for Kent and Gentlemen’s teams, but he was also a busy barrister, and his Thespian interests began taking up more and more of his time. Yardley’s batting form declined suddenly and sharply, and he played no more first-class cricket after the age of 29.

Yardley increasingly devoted his time to the stage—acting, writing, and producing—though he retained enough interest in cricket to write newspaper columns. Over the years, these became more erratic and noticeably less good-humoured. The likely reason was his deteriorating health. Gout—the curse of not only the drinking classes—often caused him pain verging on the unbearable. There was then no Atenolol to offer relief. As a descendant of one who allegedly attempted to amputate his own great toe due to gout (with fatal results), and a sufferer himself, this reviewer feels untold sympathy.

Yardley’s condition deteriorated rapidly, and he died aged 51 at The Sun Hotel, Kingston. The immediate cause was recorded as heart failure; in addition to gout, he suffered from jaundice and gastritis. He left behind a widow, Maud—20 years his junior—and four children, completely unprovided for. It was a sad end to a life once so full of promise.