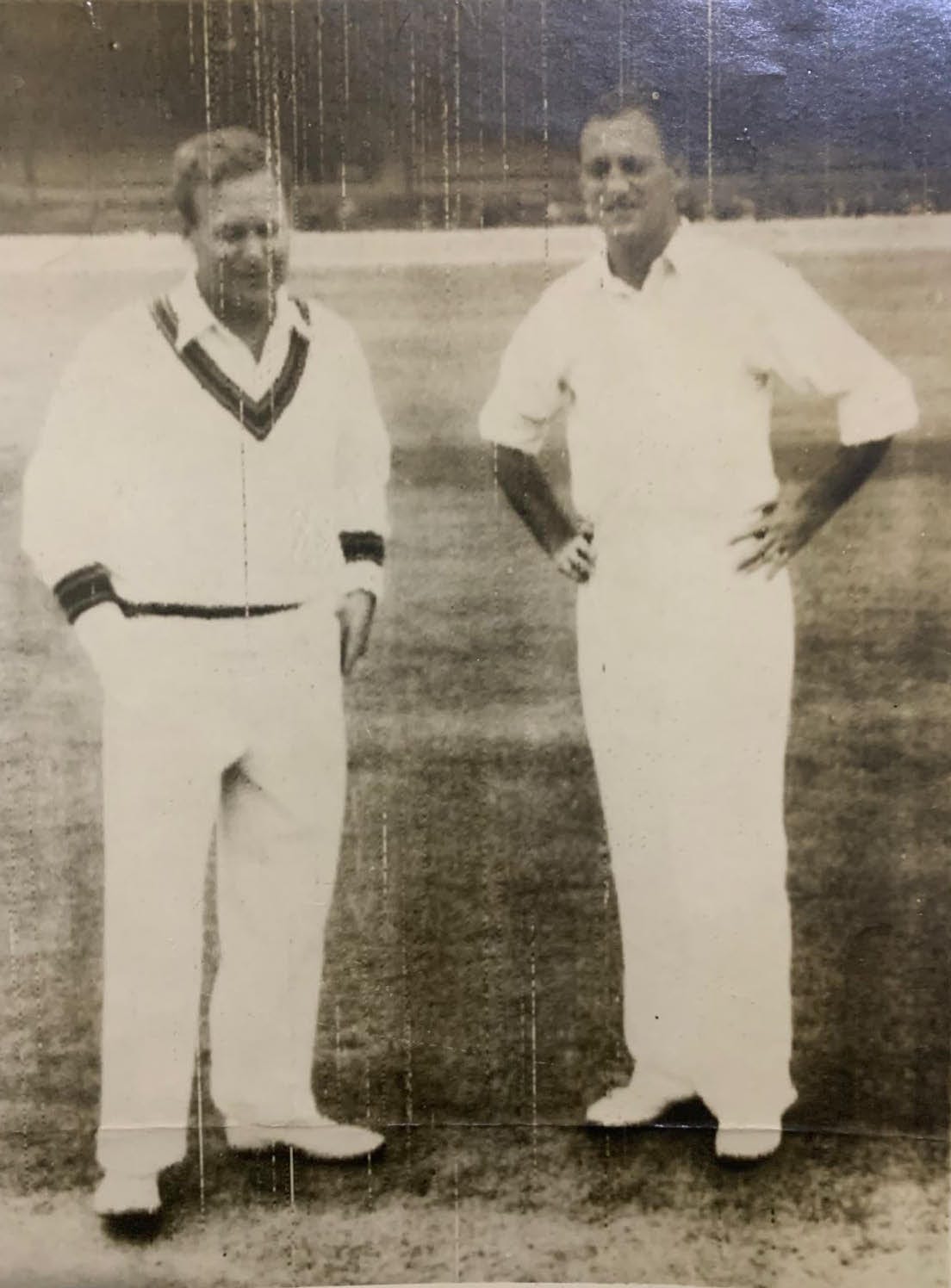

In this photograph, a recent addition to my growing collection, originally dispatched from Sydney to London by wire telegraph (hence its rather romantic indistinctness), we see Len Hutton and Arthur Morris in relaxed pose. The date is December 17, 1954, the opening day of the second Test Match of a very famous series. The arena, of course, is the SGC. As captains respectively of England and of Australian, Hutton and Morris are about to toss for choice of innings.

The First Test, in Brisbane, had concluded a week and a half earlier in a resounding triumph for the Australians, who vanquished the tourists by a full innings and 154 runs. But the gods of fortune dealt a mixed hand: The home captain, Ian Johnson, and his stalwart all-rounder Keith Miller were now both sidelined by injury, their places filled by Jim Burke and the promising Graeme Hole. England, meanwhile, were understood to be contemplating the inclusion of two spinners.

The night before the Test brought a ferocious thunderstorm, but the pitch emerged unscathed; for the very first time, it had been protected by covers. The spectators gained admittance into the ground only half an hour before the commencement, and their anticipation became astonishment when it was discovered that Alec Bedser, linchpin of England’s post-war bowling, had been omitted from the visitors’ line-up. So Hutton was going with the two spinners after all—both fellow Yorkshiremen, in Johnny Wardle and Bob Appleyard. Vic Wilson was twelfth man.

A few moments after my photograph was captured, Morris won the toss and elected to bowl, and England’s opening pair, Trevor Bailey and Len Hutton, faced up to the formidable pace of Ray Lindwall and Ron Archer. Runs were at a premium, and when Bailey succumbed to Lindwall for four, the visitors seemed to be tottering. By lunch they had inched to 34 for two, with Hutton holding the fort.

His vigil was cut short after the interval, courtesy of a brilliant catch by Alan Davidson off Bill Johnson, and the afternoon session became as much a grind as its predecessor. The crowd of 23,000 saw a stern test of character—both of the batsmen and of themselves—as England laboured to 94 for seven. At one point Frank Tyson was struck by a bouncer from Lindwall, a breach of the unwritten code between fast bowlers. Cowdrey departed for 28 after tea, leaving the last-wicket pair, Johnny Wardle and Brian Statham, to muster a defiant last stand. Wardle fell at length for 35—top score in a meagre 154.

Rain returned during the interval, but it did not dampen the intensity of the cricket. Morris, alongside Les Favell, opened Australia’s reply to the probing of Bailey and Statham. Morris had reached eighteen when he was caught at leg slip by Hutton off Bailey. His team-mates mostly followed their leader: Each of the top nine managed double figures, but none went on past fifty. In the end Australia were all out for 228, Bailey and Tyson taking four wickets apiece.

England’s second innings was defined by a masterful century from Peter May, 104 in a total of 296, setting Australia a daunting target of 334. The stage was set for Tyson to unleash his thunderbolts, and he did not disappoint, claiming six for 85 in a spell of relentless ferocity. Despite game Australian resistance, England clinched a memorable victory by 38 runs.

This triumph was not merely a cricket match won; it was a decisive moment in cricketing history. Two months later Hutton’s men completed their comeback, taking the rubber 3-1.

If you would like to contribute to this newsletter, please either respond to the email in which you received it, or leave a comment below.