The First Centenary Test: Part III

Jim Ledbetter on day two of the First Test of the 1921 Ashes

Monday, May 30

Once again heavy rain on Sunday and early Monday morning failed to dampen the enthusiasm of the Nottingham public, as over 20,000 spectators took their places in the Trent Bridge ground, the gates being opened as early as 9.00am. Despite the wet weather, play began promptly at 11 o’clock, with Douglas immediately introducing spin at both ends, bringing on Woolley and Rhodes, who were to bowl throughout the 75-minute morning session. Wilfred Rhodes received a special cheer as he commenced bowling for the first time in the match, having been strangely overlooked by his captain on the first day.

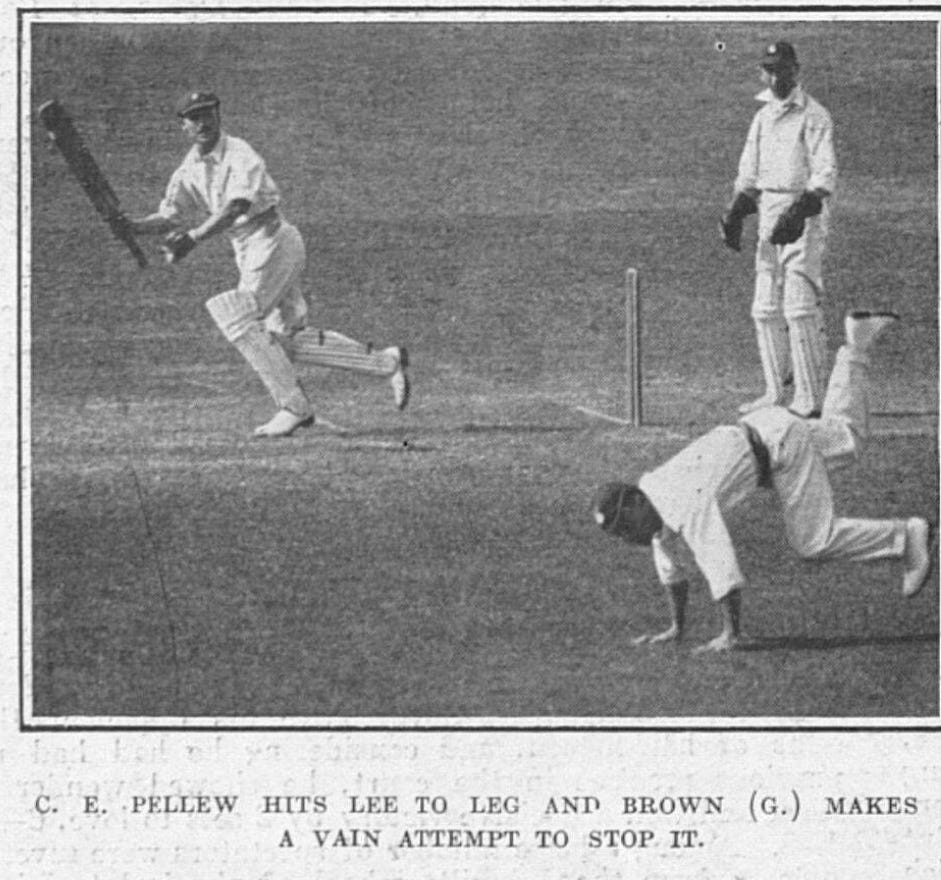

It was at once apparent that both he and Woolley were extracting both lift and turn from the pitch. The England bowlers soon achieved their initial objective as Pellew, having added only four to his overnight total, became Rhodes’ first victim in only the fourth over of the day, defeated by the sharp turn of the ball as he attempted to hit it to leg. The ball, hitting the edge of the bat, presented the bowler with a simple return catch. Further encouragement came with the dismissal of Andrews, also caught and bowled by Rhodes and Hendry’s apparent inability to score runs, 15 minutes elapsing before he struck his first run in Test cricket.

Unfortunately for England, runs were coming far too quickly at the other end as Carter, the nightwatchman, took full advantage of the all too frequent short deliveries of England’s spin attack, using his well-known unorthodox ‘shovel’ shot, a scoop in the direction of square leg, to score the bulk of his 33 priceless runs. It was to cause Strudwick to lament, “When shall we learn to stop these favourite shots of different batsmen?”

Carter eventually departed, bowled leg-stump by Woolley, but his 65 minutes at the crease had helped his side move from a moderate lead of 40 to a virtual match-winning lead of 100 runs. England’s miserable morning was rounded off by a final onslaught by the last wicket pair of Hendry and McDonald. The arrival of McDonald prompted Hendry to throw caution to the winds, which quickly earned him two boundaries off Woolley. McDonald, not to be outdone, joined in the fun, hitting ten runs off Rhodes’ final over before skying a catch to gully. A further precious 20 runs had been added in the final 15 minutes of the innings, giving the Australians an impressive first innings lead of 120 runs. It had not been a good morning for England, especially after achieving an early breakthrough. It was generally felt that the England bowlers should have made more use of the conditions, for the pitch, if never difficult, had provided some encouragement for the spinners.

The Australians could feel well satisfied with a lead of 120 runs and the chance of almost an hour’s bowling before lunch on a pitch which still appeared to give assistance to the bowlers. Sidney Smith recounts that MacLaren, sitting next to him in the pavilion, remarked that the match would be all over by 6.30pm and that Australia would win by an innings. Smith disagreed, but admitted, “I felt we had the game in the hollow of our hand.”

In an attempt to minimise the threat of the Australian pace attack, Douglas called for the heavy roller. The move paid off initially, for it was soon apparent that the pitch was still sufficiently wet and soft for neither Gregory or McDonald to obtain much assistance from it before lunch. Armstrong, quickly appreciating the situation, replaced Gregory after only two overs, bringing on Macartney in an attempt to see if the pitch would give similar assistance to the spinner, as it had done earlier in the day. At the other end, McDonald also reduced his pace, concentrating on length, line and variations of pace, reaping his reward with the wicket of Holmes after 40 minutes play with the England score on 23. The England opener, deceived by the pace, played too soon, putting the ball up to Taylor at mid-on, who rolling over, clung on to the ball. The remaining 25 minutes before the luncheon interval produced only five more runs, as Tyldesley, facing a pair on his Test debut, took 15 minutes to get off the mark.

The morning session had ended with Gregory being brought back for McDonald, whose controlled accuracy had earned him the impressive figures of one wicket for seven runs in his first nine overs. At the other end, Armstrong had bowled five overs for only four runs. This pattern of attack continued throughout the afternoon, Armstrong bowling unchanged from the Radcliffe Road end with Gregory and McDonald operating in short spells at the Pavilion end. Pressure was applied immediately with the introduction of Taylor and Collins, stationed at short mid-on and mid-off. Pegged down at one end by the accuracy of Armstrong and facing the hostile pace of Gregory and McDonald at the other, the England batsmen found runs hard to come by against an accurately placed field.

It was also noticeable that both Australia’s fast bowlers had begun to make increasing use of the short-pitched delivery. It was from such as ball that England lost her second wicket in controversial fashion. Tyldesley, having been at the wicket for 40 minutes for his seven runs, attempted to pull a short ball from Gregory (described in Wisden as a fast long hop). Misjudging both the pace and bounce, he was struck a fearsome blow on the jaw. Revived by several glasses of water, he was in no condition to continue his innings and was assisted from the field. Only then did it become clear that he had been given out bowled, the ball having trickled onto the stumps, removing a bail.

A tense situation was not helped by Hendren coming in and patting the turf halfway down the wicket. The crowd, incensed by the manner of Tyldesley’s dismissal, demanded Gregory’s removal. The Times was not amused. “Neither the advice tendered by the crowd to Armstrong, nor the cheering when he took it, was justified. After all, he merely substituted McDonald for Gregory, and the frying pan is proverbially cooler than the fire.”

There was to be no respite for the England batsmen. Armstrong had virtually closed up one end with his policy of containment. As in the first innings, his approach was to bear fruit. Hendren, who had won the crowd’s approval by his determination to break this stranglehold by looking for quick singles, attempted one too many. Ignoring the oft-stated “never run for a misfield,” he set off after a drive was half-stopped by the bowler, Armstrong. Realising that Macartney at mid-off had gathered the ball, he sent Knight back. Knight, too far down to retrieve his ground, was left stranded as Macartney coolly walked over and broke the wicket.

For Knight, who in his first Test, had run up his side’s highest innings, this was a personal tragedy, for he had begun to show glimpses of the flair and promise which had earned him his England place. The incident also seemed to affect Hendren, who, conscious of his contribution to his partner’s dismissal, departed two overs later, having hit over a McDonald half-volley, his innings of 40 minutes consisting entirely of singles.

Now followed a war of attrition as Woolley and Douglas attempted to retrieve a desperate situation against an Australian attack, growing increasingly hostile as the match went Australia’s way. Thirteen runs were added in 40 minutes before Douglas, surprised by a sharply kicking delivery from McDonald, was caught at second slip off the shoulder of his bat. Gregory, brought back into the attack and seemingly spurred on by the taunts of the crowd, gave the new batsman, Jupp, a difficult time. After an inadvertent snick for four over the keeper’s head, Jupp spent the remainder of the same over, “protecting his head from damage by short deliveries”, according to a local press report.

Woolley too received a sharp blow on the arm as he struggled to survive. At one time, he was restricted to one single in 30 minutes, “pursuing tactics entirely foreign to his nature,” observed the Daily Guardian. A glimpse of his usual style surfaced only in Armstrong’s final over before tea, when the Australian captain was struck for a magnificent six over long-on to bring the 100 up in 185 minutes. Despite this blow, Armstrong’s unchanged spell of 22 overs in the afternoon session had yielded only 29 runs and his lack of wickets was more that compensated for by his unrelenting pressure on the England batsmen. It was a fine bowling spell, reminiscent of his performance in the 1905 Trent Bridge Test, when his 52 second innings overs yielded only 67 runs.

After tea, the England batsmen resumed, with 16 runs still required to make Australia bat again, facing Gregory and Hendry, who was bowling for the first time in a Test Match. Still ten runs short of this target, Jupp after sharing in his side’s biggest partnership of the match, a sixth-wicket stand which realised 34 runs, fell ingloriously to Gregory. Having edged the bowler for four through the slips, he attempted to drive the next delivery but only succeeded in giving Pellew at mid-off a simple catch. Woolley and Rhodes averted an innings defeat, although the latter survived a difficult chance off Hendry, Gregory at first slip getting a hand to the ball, “that generally suffices,” noted The Times, mindful of Gregory’s reputation as a slip fielder but on this rare occasion, he failed to take the catch. The partnership was finally broken when Woolley, after a stay of 115 minutes for his 34 runs, became Hendry’s first Test victim, Carter making a good catch.

Hendry had little time to wait for his second Test wicket, Strudwick being bowled by his next delivery, becoming the first batsman to record a pair in a Trent Bridge Test. Hendry, with Howell coming to the crease, had the distinct possibility of a hat-trick on his first Test appearance. Howell survived, but first Rhodes, caught behind off a short delivery, and then Richmond, comprehensively bowled (the bail travelling a full 30 yards), were snapped up by McDonald to give him his best Test figures so far, five wickets for 32 runs. In 55 minutes after tea, England had lost their five remaining wickets for 43 runs.

Australia went in at six o’clock, requiring 28 runs to win with 30 minutes of the second day remaining. With Collins suffering from what was eventually diagnosed as a broken thumb, Macartney joined Bardsley as Australia’s opening partner. Any thoughts that the match might go into the third day, were rapidly dispelled as the runs were scored off a mere 37 deliveries, Macartney making the winning hit with a late cut for four off Jupp. It appeared as if the England captain was just as keen to avoid a third day’s play as the Australians, for he immediately put on Richmond and Jupp to open the bowling, It seemed that Douglas, as Joe Darling in the 1905 Test at Trent Bridge, who had refused to appeal against the light with Australia well beaten, accepted that his side had been beaten fair and square and was not prepared to force the game into a third day, when England may have avoided defeat through the intervention of the weather.

This English defeat, the scale and the manner of it, was to throw English cricket into confusion for the remainder of the series. Never before had an England XI lost six consecutive Tests against Australia. England’s ten-wicket defeat equalled their worst-ever defeat at home since that at Lord’s in 1899. On only one previous occasion, in 1888, had England lost the first Test of a series in England and that in a Test in which the weather played a significant part in the outcome. England’s defeat after only 610 minutes of play ranked with this defeat at Lord’s in 1888, but in 1921 there were no freak conditions to provide any excuse in this contest. Only in the famous Test of 1882 at The Oval, when Spofforth ran through the England side in both innings, had an England batting side been routed in such a manner by an Australian bowling attack in England. The manner of England’s defeat was reflected in the following day’s newspaper headlines with the constant use of “debacle” and “outplayed”. One year later the defeat still rankled. Wisden’s observation was typical. “Never in the history of Test matches has English cricket been made to look quite so poor as in the first game of the series last summer. We were not merely beaten, but overwhelmed.”

Few were to emerge then or subsequently with reputations intact. Literally overnight it was forgotten that both the selectors and the XI chosen had received almost unanimous support. Recriminations flew backwards and forwards as both the team and Selectors were castigated. The Cricketer declared it would make a clean sweep of the side, excepting Douglas, Knight, Woolley and Hendren. The local Nottingham newspaper, the Journal, went even further when it confessed that “when the team was chosen we gave it our benediction, now the match is over we can reasonably lift the curtain of restraint. We never had the slightest confidence that England would win the Centenary Test.”

Pressure was also put on the selectors to find a winning side. The Times thundered that “it is almost a matter of national honour that the Australians should be beaten at Lord’s.” The selectors went along with the tide of criticism. Only five players retained their places for the Lord’s Test. By the end of the series, no less than 30 players, more than in any other series, then and since, had been tried with 16 players making their debut. Seventeen selected players were to appear in only one Test. For seven of them, Dipper, Ducat, Durston, A.J.Evans, Hardinge, C.W.L.Parker and Richmond, this was to be their sole Test appearance. Woolley and Douglas alone retained their places throughout the series, with the latter giving way as captain to Tennyson after the Lord’s Test. Even so, there were several glaring omissions. The dropping of Holmes after the First Test was extremely harsh, and the continual overlooking of Gunn (who true to character, hit a marvellous 117 against Middlesex at Lord’s in the week after the Trent Bridge Test) is hard to fathom. Not that the press could make up their minds either. No less than 40 possibles were put forward as candidates for the Second Test after England’s defeat.

All the Selectors’ efforts were in vain. Australia went on to win the next two Tests, eventually winning the series by three matches to nil. In retrospect, given the peculiar circumstances of that particular year, it is hard to imagine an England side capable of beating such a formidable Australian combination. Sidney Smith’s summary of why his Australian side was victorious at Trent Bridge could equally apply as an explanation of Australia’s convincing retention of the Ashes in 1921. “Our fast men bowled in Test match style and faster than they had bowled up to that day; our skipper handled his side well; our batting was fairly consistent; our fielding was an object lesson to any team. The Englishmen lacked cohesion and with one or two exceptions, were absolutely at sea to fast bowling; and their fielding was not up to Test match standard.”

C.G. Macartney, in his autobiography, My Cricketing Days, published in 1930, gave a shrewd analysis of the reasons for Australia’s undoubted supremacy, writing that Australia’s retention of the Ashes was not unexpected. He compared the poor condition of English cricket at the time, the consequence of the loss of many potential cricketers in the Great War, the temporary loss of Hobbs and Hearne, the lack of an intervening season between the two series, which restricted the introduction of new talent, to Australia’s more fortunate set of circumstances at that point in time.

In particular he stressed the contribution of the AIF side which discovered and matured “sufficient men of Test ability” to allow Australia to maintain a side of high quality after the war. This was indeed a major factor in Australia’s success, for in the space of a year, this team gained experience in both England and South Africa, playing in all 39 First-class matches. Even on their tour of England in 1919, they were permitted to play three-day matches, whilst the Championship for that one year consisted of two-day games. The key role of the AIF side in Australia’s post-war success was supported by Arthur Mailey (10 for 66 and All That), who observed that the AIF emerged as one of the strongest teams in the history of Australian cricket and that its fighting spirit and amazing camaraderie gave Australian cricket a badly needed shot in the arm in the post-war years. All this at a time when English cricket was still struggling to organise itself after the war.

The first Centenary Test has been generally forgotten as a game which celebrated the first important anniversary of Test cricket, coming as it did at a most inopportune moment in the fortunes of the game in England. It is the scale, manner and significance of the English defeat which remained in the minds of both the game’s authorities and the cricketing public for many years to come.

This article first appeared in The Cricket Statistician for Winter 1997. To join the Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians, and subscribe to the journal, please visit our website: