I recently acquired a photograph of the opening stand between Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe on day one of the Fifth Test at The Oval in 1926. Less storied than their second-innings efforts, it prompted me to delve into the annals, refreshing my understanding of the events of that day.

The previous four Tests had all ended in draws, prompting the decision to make the decider timeless. It would extend as long as needed to secure a result. The professionals were compensated £33 each for the marathon match, while the twelfth man received £22. Amateurs could claim a first-class rail fare up to £2. The umpires were allotted £20, and the diligent scorers £7 to £10. Admission for the eager public was three shillings.

Wilfred Rhodes, at the age of forty-eight, was brought in to replace his Yorkshire colleague Norman Kilner. Additionally, a new captain was named: Percy Chapman took over from Arthur Carr. Then England’s wicketkeeper, George Brown, injured his thumb, necessitating the last-minute inclusion of Herbert Strudwick, aged forty-six.

The queue in Kennington began to form at five o’clock the evening before, led by a blind man and his wife and daughter. Close on his heels was a young lad of fifteen. By midnight, approximately 600 individuals had gathered at the four gates. They were kept waiting until half past eight the next morning. By the start of play, however, only 10,000 seats were occupied. The hype had been, if anything, too great: So many had despaired of the possibility of securing a ticket that thousands remained unsold.

Chapman, tossing a gold sovereign, won the toss and elected to bat. The omens were favorable, for England had lost only once in fourteen Test Matches at this ground over forty years.

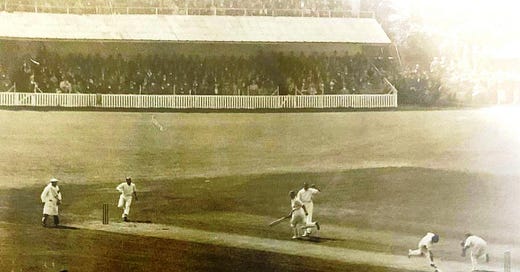

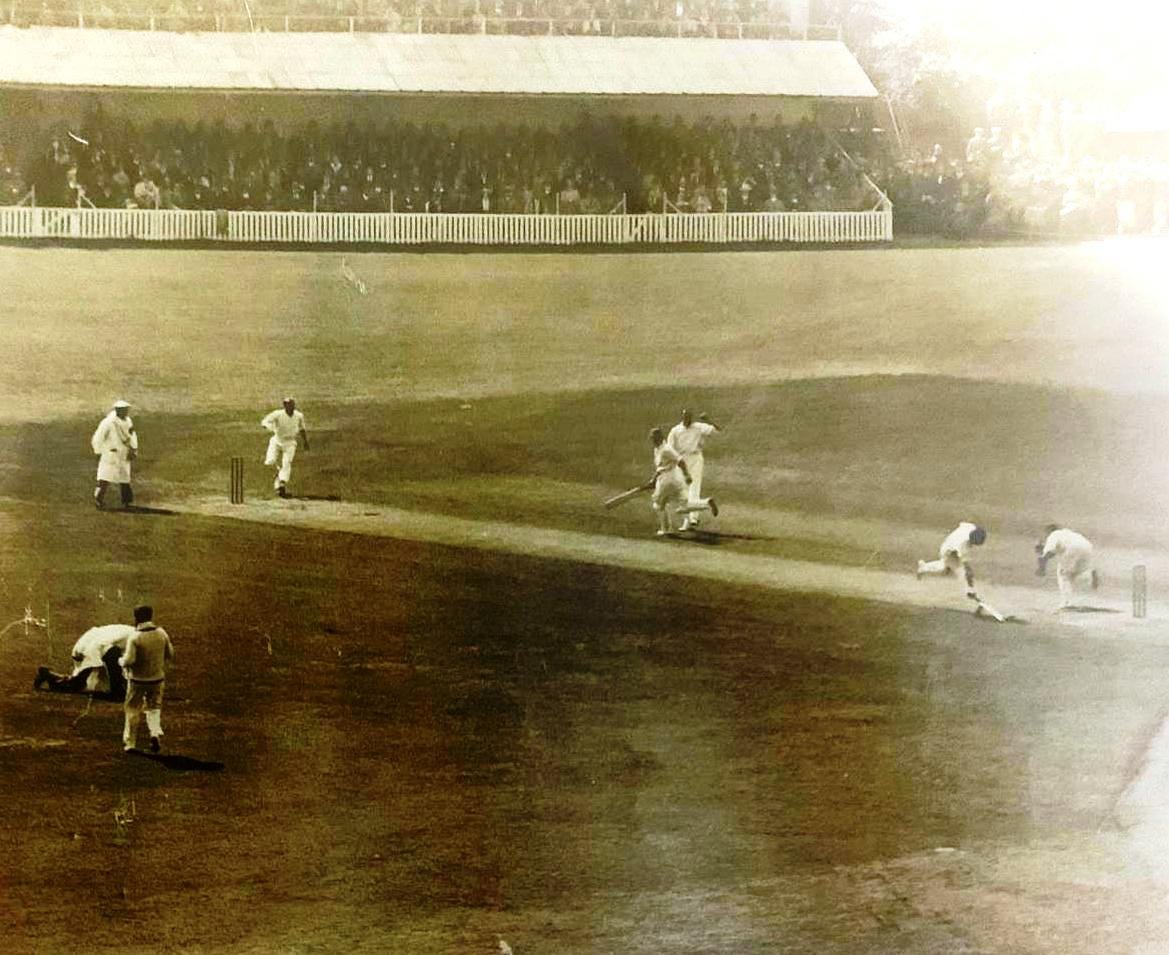

Hobbs and Sutcliffe began their innings with steady composure. The only incident of note early on was Hobbs’s objection to a kite flag near the pavilion, which was swiftly taken down. At some point during these early exchanges, Gregory ran in and bowled to Hobbs, and a few beats later, someone snapped the photograph I now hold in my hands.

One thing I find particularly striking thing about it: It seems to belie the reputation of England’s famous opening pair for their understanding between the wickets. Sutcliffe has all but made his ground, but his partner is only halfway down. Had the fielder thrown to the other end, a direct hit would surely have done for Hobbs. As it was, he was eventually bowled by a Mailey full-toss for 37, ending a fine opening stand of 53.

By lunch, the crowd had swelled to 15,000. Sutcliffe batted with determined resilience until he was struck in the face by a ball from Mailey—an unfortunate incident that no doubt contributed to his dismissal next ball. He had amassed 76 runs in three hours and 23 minutes: a testament to his endurance and skill, and a preview of the great things he would achieve on days two and three.

By the close of play, England had been bowled out for 280, while Australia stood at eighty for four. They would be dismissed for 302. Then the stuff of legend: Hobbs and Sutcliffe, with a magnificent first-wicket partnership of 172, set the stage for an English victory by 289 runs. Wilfred Rhodes also played a pivotal role, taking four wickets for 44 runs in twenty overs. The match concluded on the fourth day, rendering the timeless aspect nugatory.

If you would like to contribute to this newsletter, please either respond to the email in which you received it, or leave a comment below.