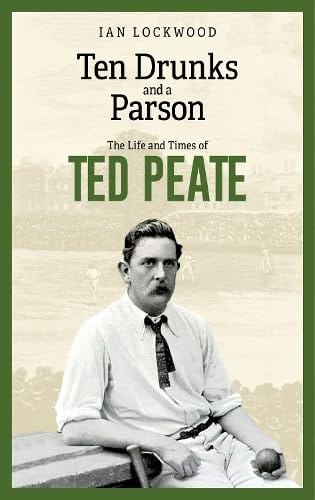

He lies in an unmarked grave in Yeadon Cemetery, where ten other Yorkshire players rest beneath solemn, inscribed stones. A largely forgotten figure in the annals of Yorkshire and England’s cricketing past, his name is now scarcely murmured beyond the circles of those who take pains to remember. Yet it was his dismissal at the Oval in 1882 that sounded the death knell for English cricket and heralded the birth of the Ashes.

In his prime Ted Peate was the finest spin bowler in the world, his art a rare alchemy of flight, break and guile. He was the pioneer of that great lineage of Yorkshire left-arm spinners which is still invoked with reverence: Bobby Peel, Wilfred Rhodes, Hedley Verity, Johnny Wardle…

In 1900, just nine days after his forty-fifth birthday, Peate died in Newlay, Horsforth, slipping from life as quietly as he had faded from memory. His family, of scant means, could not afford a headstone. And so the years have passed, and the grass has grown over him.

Ian Lockwood, author of Ten Drunks and a Parson: The Life and Times of Ted Peate, does not confine himself to Peate’s prowess as a bowler. As its title suggests, this book paints on a broader canvass—a time of radical change, and a life as colorful as it was chaotic, marked by a fondness for drink that, in the end, proved more formidable than any opposing batsman.

“Ten drunks and a parson,” Lord Hawke declared, disapprovingly, when he assumed the Yorkshire captaincy in the 1880s and set about reforming a squad whose wayward habits had dulled its performances. Peate was cast aside in 1887, dismissed at the age of thirty-two, despite having been Yorkshire’s leading wicket-taker in seven of his eight seasons. Hawke later described it as “one of my saddest tasks.” But Peate bore no ill will. Whenever he encountered his old captain, he greeted him with the same slow, unwavering courtesy: “Good morning, my lord. I hope you are as well as I am.”

Yet, in truth, Peate was not well at all. His eyesight failed him, his girth expanded, his health waned. Pneumonia finally took him, and Wisden, with paternal severity, reflected that “he would have lasted longer had he ordered his life more carefully.”

Even as his body declined, Peate continued to ply his trade in lower-level cricket in Leeds and Skipton. He later served as Headingley’s first groundsman.

And now, all these years later, I ask the question: Should his grave remain unknown, unmarked, and unsung? If you agree that it should not, buy a copy of Lockwood’s book, all of whose proceeds will go to fund a memorial.